Greek Temple Architecture

With its rectangular stone platform, front and back porches (the pronaos and the opisthodomos) and rows of columns, the Parthenon was a commanding example of Greek temple architecture. Typically, the people of ancient Greece did not worship inside their temples as we do today. Instead, the interior room (the naos or the cella) was relatively small, housing just a statue of the deity the temple was built to honor. Worshippers gathered outside, entering only to bring offerings to the statue.

The temples of classical Greece all shared the same general form: Rows of columns supporting a horizontal entablature (a kind of decorative molding) and a triangular roof. At each end of the roof, above the entablature, was a triangular space known as the pediment, into which sculptors squeezed elaborate scenes. On the Parthenon, for example, the pediment sculptures show the birth of Athena on one end and a battle between Athena and Poseidon on the other.

So that people standing on the ground could see them, these pediment sculptures were usually painted bright colors and were arrayed on a solid blue or red background. This paint has faded with age; as a result, the pieces of classical temples that survive today appear to be made of white marble alone.

Proportion and Perspective

The architects of classical Greece came up with many sophisticated techniques to make their buildings look perfectly even. They crafted horizontal planes with a very slight upward U-shape and columns that were fatter in the middle than at the ends. Without these innovations, the buildings would appear to sag; with them, they looked flawless and majestic.

Ancient Greek Sculpture

Not many classical statues or sculptures survive today. Stone statues broke easily, and metal ones were often melted for re-use. However, we know that Greek sculptors such as Phidias and Polykleitos in the 5th century and Praxiteles, Skopas and Lysippos in the 4th century had figured out how to apply the rules of anatomy and perspective to the human form just as their counterparts applied them to buildings. Earlier statues of people had looked awkward and fake, but by the classical period they looked natural, almost at ease. They even had realistic-looking facial expressions.

One of the most celebrated Greek sculptures is the Venus de Milo, carved in 100 B.C. during the Hellenistic Age by the little-known Alexandros of Antioch. She was discovered in 1820 on the island of Melos.

Ancient Greek Pottery

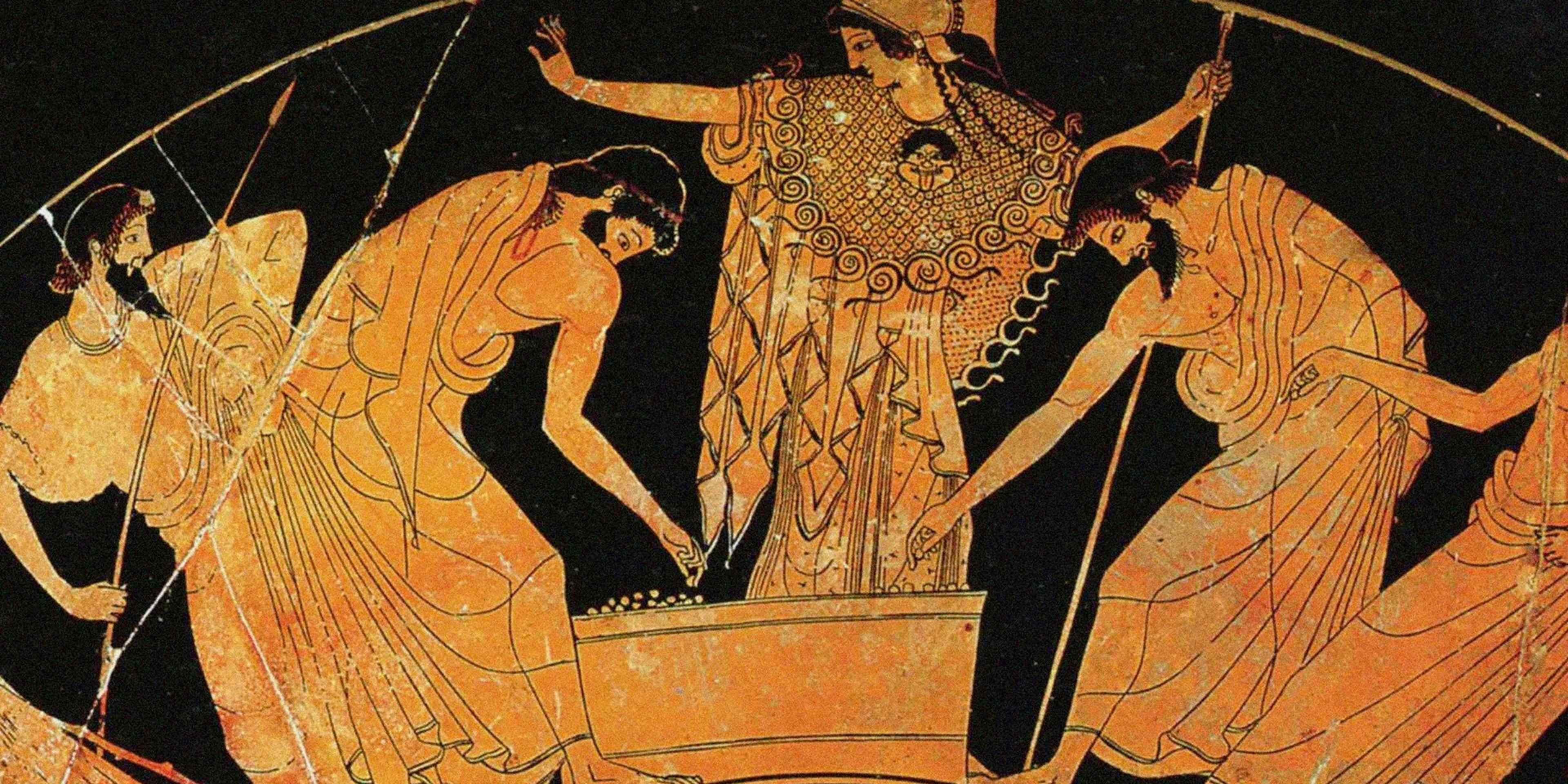

Classical Greek pottery was perhaps the most utilitarian of the era’s art forms. People offered small terra cotta figurines as gifts to gods and goddesses, buried them with the dead and gave them to their children as toys. They also used clay pots, jars and vases for almost everything. These were painted with religious or mythological scenes that, like the era’s statues, grew more sophisticated and realistic over time.

Much of our knowledge of classical Greek art comes from objects made of stone and clay that have survived for thousands of years. However, we can infer that the themes we see in these works–an emphasis on pattern and order, perspective and proportion and man himself–appeared as well in less-durable creations such as ancient Greek paintings and drawings.