For Barack Obama, stopping the inexorable advance of global warming

felt like an almost personal mission.

Despite tangible accomplishments—bringing China to the table during

the Paris climate change conference or advancing clean air technology

here in the U.S., the president and his team still question if their

efforts—if the world’s efforts—will be enough to turn back the

tide and save the planet.

Well, it’s a matter of life and death. I mean it’s very

simple—it really is. This is the first president [who] recognizes that

this is a generational moral responsibility, that we will be judged on

whether or not we heeded the evidence and responded.

During the campaign, this was an issue that [the president] was

focused on and intellectually invested in understanding. He has seen

what has happened over the last several years, which is that the

science continues to tell us that…the pace of this problem is

significantly outstripping the steps the world is taking to try to

address it. I think that has motivated him.

My friend and colleague in the United States Senate, Pat Moynihan,

from New York, had a great saying: “Everybody’s entitled

to their own opinion but you’re not entitled to your own

facts.” Report after report has documented how the science

works.

The president led an energy revolution in many ways, using the

Recovery Act to seed renewable energy, using his leverage with the

auto industry to raise fuel efficiency standards in a historic way,

using his authority through the EPA to ratchet down greenhouse gases,

bringing the world together around the Paris Climate Change Agreement.

In December of 2009, in Copenhagen, more than 100 world leaders,

including Barack Obama, met to try to forge an agreement to help heal

the planet. Despite high hopes, the conference was marred by discord,

and the non-binding resolution that emerged has been widely seen as

anemic, at best. But looking back at Denmark, the president and his

team now say the conference may have planted the seeds that led to

more fruitful advances years down the line.

At the end of 2009, when the president and then-Secretary of State

Hillary Clinton went to the Copenhagen climate talks, they showed up

in a chaotic environment. There was no semblance of order. It was so

bad that [they] had to run around the convention hall to find the

Chinese and the Indians and the Brazilians, the delegations that had

holed up in a meeting room to try to avoid the president. He had to

literally bust in on the meeting, he and Secretary Clinton, to sit

down to say, “Look, we’ve got to find some path

forward.”

Copenhagen crashed, and it crashed largely because China and the G77

countries [a group of developing countries formed in 1964], felt there

was no methodology on the table that recognized their challenges. That

the developed world was dumping responsibility on them. And there was

this great divide. When the president made me his secretary of state,

it was clear to me that if we were going to move forward, we had to

have China.

Copenhagen is largely written off as a failure, but the seeds of

progress were planted in the president and Secretary Clinton’s

engagement there. What came out of that failed negotiation was a sense

that if we were going to build a new global coalition to fight climate

change, it was going to have to look and feel different than [what] we

had been doing.

For decades, this had been fought as two teams: developed and

developing countries. And the U.S. and China were captains of the

teams and they came and butted heads. And the developing countries

said, “It’s on you guys to combat climate change

and…that just wasn’t going to work. And that was what was

clear out of Copenhagen. If we were going to change this, we were

going to have to mount a new global effort to get there.

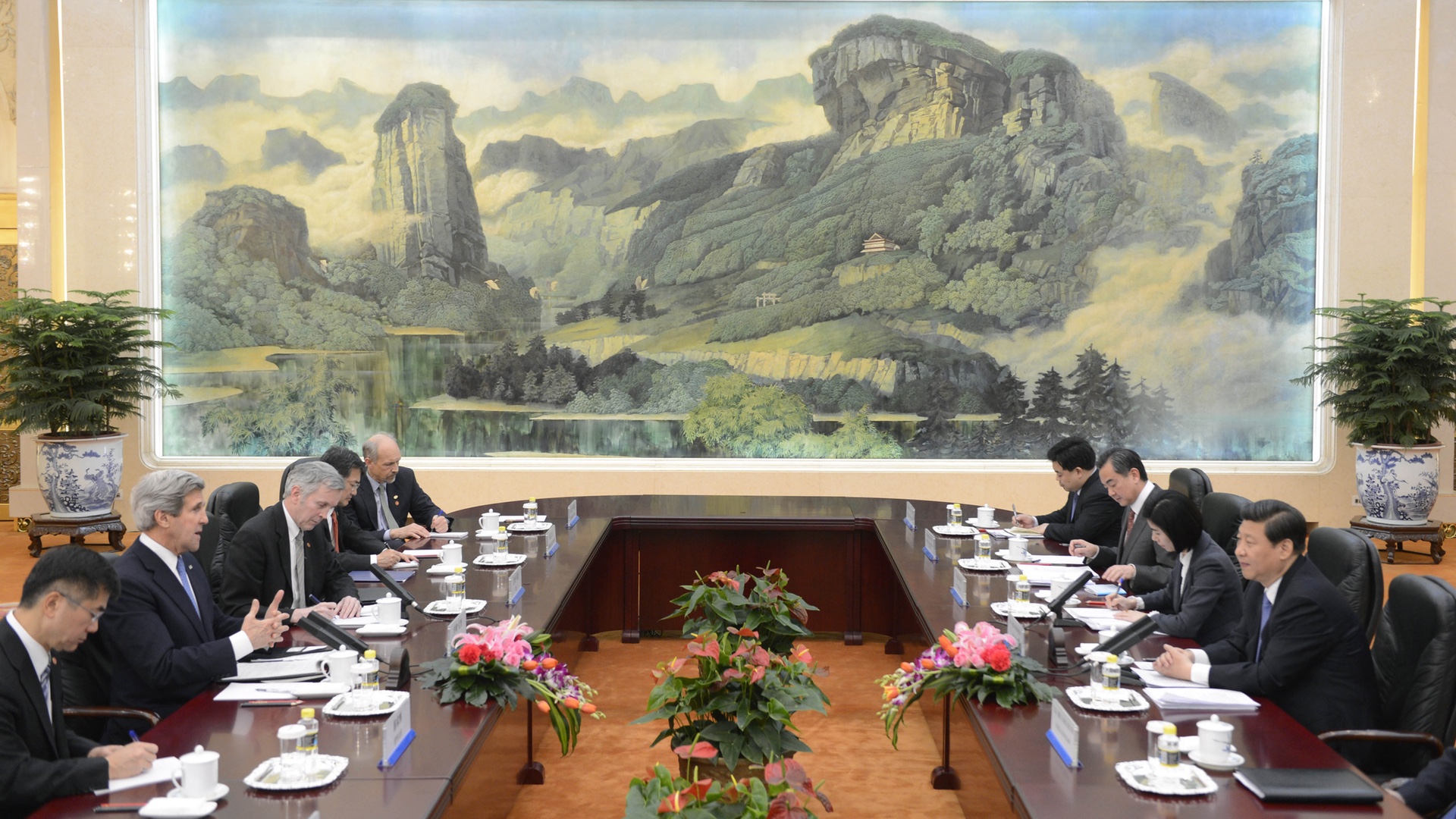

One of Kerry’s first major trips as secretary of state was to go

to China, in April of 2013. On the table: hammering out the first

steps of a new partnership between that country and the U.S. to work

together to beat back climate change.

Within about a month and a half of being secretary, I went to China.

We got them to agree to create a working group with a view to trying

to get in a place where our two presidents, President Xi and President

Obama, could stand up before the world and say, “Here we are,

China and the United States. [We] disagreed to the point of failure in

Copenhagen; now we’re agreeing we have to move forward.”

That was a sea change, dramatic, monumental moment of transformation

on this issue. And when President Xi and President Obama announced our

joint intended reduction levels, every other country knew, “Wow,

something serious is happening.”

Despite the BP oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico in April of 2010,

legislation to put a cap on carbon emissions, championed by the

president and then-Senator John Kerry, died on the vine in an

increasingly partisan Senate. Obama was determined to do better his

second term, with or without the help of Congress.

First and foremost, we needed to move the United States from a laggard

on this issue to a leader domestically. The president tried on the cap

and trade front and failed the first term. [He] decided in the second

term we were going to move away from Congress and use the tools we

could domestically. We launched a climate action plan in 2013 and used

tools across our economy and our industry to try to increase fuel

economy of vehicles, increase energy efficiency of our buildings and

factories, and take carbon pollution out of the power sector with the

Clean Power Plan. That effort helped change the perception of the U.S.

as actually leading, and putting our money where our mouth is.

The second big piece was the U.S.- China joint statement in 2014,

where the president and his team worked behind the scenes with the

Chinese to come to an announcement where you had the two captains of

the opposing teams standing together and saying, “We’re

going to change the playing field. We’re going to jointly

announce ambitious climate targets. There is not a top-down effort to

dictate what we will do but we’re both going to do

something.” That helped unlock a process of two years of intense

diplomacy with countries around the world, to try to pull those

countries forward to support a global coalition to Paris.

In the months and days leading up to the monumental United Nations

conference on climate change, to be held in Paris at the end of 2015,

Secretary of State Kerry traveled the globe, priming attendees

beforehand, keen to avoid another rehash of the failure in Copenhagen.

We were bringing countries to the table, teeing up Paris. And when the

time to go to Paris came, I spent 10 [or more] days negotiating every

day, working with countries, bringing India, bringing Korea, Japan,

other countries to the table so we could work through the differences

and get an agreement. And all the leaders came on the first day. That

was a big debate: Do they come the first day [or] at the end? The

decision was made to come the first day, and it set it into motion and

was very dramatic, with all of these leaders there saying, “We

have to get this done.” It created an energy that was essential

to the negotiations.

The president flew over to Paris on the first day, spoke to the

conference and then had meetings with key countries: the Chinese, the

Indians, trying to say, “Look, our negotiators are going to be

here for the next 10 days. But can we try to find some agreement that,

when push comes to shove and things get tough, we look each other in

the eye and say, ‘Okay, now is the time when our set of countries is

going to come together and really solve this.’” It

wasn’t easy. Part of the way we managed…that second week,

when we were all in Paris in negotiating rooms, [was that] every

evening or every morning, depending on the complicated time zones,

[the president was] making calls [from Washington] to the Brazilians,

or the Indians, or, ultimately, the Chinese. He had a couple of very

important interactions [by phone], particularly with President Xi of

China, near the end of the conference, where that sense of

understanding was cashed in to say, “Okay, now’s the time.

We need to tell our negotiators, we need to come together, we need to

lock it down. Whatever small details they can’t agree on,

it’s time to put them to bed.”

There’s nothing as exciting—and nerve wracking—as a crucial game

going into overtime on the last day of the playoffs. That was

essentially the situation on the final afternoon of the Paris

Conference, on December 12, 2015. The issue at stake: a matter of

semantics, that happened to mean everything.

The thing that was most harrowing in those last couple of days—we are

negotiating on the ground with the president talking to heads of

state, [we] had found landing zones on all of the key issues, the

financial component, transparency, and thought, “Okay, maybe

we’ve landed here. Maybe this will finally work.” The

conference was supposed to end on Friday but it didn’t, so we

woke up on Saturday morning and the French, as the conveners, were

going to release a final text with the idea that this was the

take-it-or-leave-it text. And we would all agree, or not, later in the

day on Saturday.

So we woke up, [and] we thought we were in the right place. We got a

text around noon. We came back to the room with the team running

through the text. And Secretary Kerry, Todd Stern [U.S. special envoy

for climate change] and I were there, getting input—Does everything look okay? All of the sudden, somebody came in and said, “We’ve

got a problem.” One of the sentences that we had understood

would say, “the parties should do the following

things” said “the parties shall do the following

things.” That distinction, between should and

shall, had very significant legal consequences. And we had

all agreed that it was going to say should and not

shall. So we had a harrowing half an hour, 45 minutes, where

we tried to understand what was going on. We connected with the French

and confirmed that this was a mistake, that it was supposed to reflect

what we had all agreed and that they were going to find a way to fix

it. But for a period there…all of our hearts dropped. We thought

that maybe we were going to lose this very delicately put together

effort.

I can tell you it was a very dramatic moment when the agreement was

gaveled into effect after all these years of effort—186 countries had

signed up, each with their own plan to reduce emissions. And

we’re on our plan. We’re ahead of schedule. We’re

actually meeting every target we’ve set.

In August of 2015, the president announced his Clean Power Plan, in an

effort to reduce carbon pollution from the power sector in the United

States.

It’s the single biggest thing any president has ever done to try

to combat climate change. It was years in the making and it reflected

the core of the president’s effort to combat this existential

threat. So we’re walking over to the East Room for him to make

this announcement. [It’s] a big opportunity, really exciting,

and the president pulls out an article from Science that he

had been reading the night before, about the fact that the climate

crisis was getting worse. And he said, “You know, this is really

getting to me. We’re not doing enough. We’re not moving

fast enough.” And he was clearly affected by it. And when we

walked over to the East Room and met up with Gina McCarthy, the EPA

administrator, he didn’t say, “Congratulations. This is

really exciting. I’m really glad we got to this.” Instead,

he pulled Gina over and said, “Have you seen this article?

You’ve got to read this article. You’ve got to tell me

what you think of it and we’ve got to figure out what more we

can do.” Up until he walked on stage he was focused on the fact

that we weren’t doing enough.

No president has set aside as many square kilometers of ocean for

marine preserves. No president has ever before set aside as much land

for parks and for preservation. No president has ever been as forward

leaning on protecting the environment, whether the shift from fossil

fuels to the National Climate Action Plan [enacted in 2013 to cut

carbon pollution], to the power plant regulations to the automobile

and truck standards, to efficiency standards.

The way the president thinks about the need for us to tackle [this

issue] is different from any other issue I’ve worked with him

on. The way he describes it is, “Look, on education reform or

job creation, [or] the economy…progress is frustrating.

It’s too slow, it’s halting, but you can see that

we’re moving in a positive direction. With climate change,

that’s not true. Things are getting worse and the pace of that

is increasing to the degree that we actually [will] face a point in

time—hopefully, we have not already gotten there—where…there is

such a thing as being too late. And we may have already reached that

time but if we haven’t, we need to do everything we can to get

ahead of this problem because it is a unique threat.” He talks

about this issue and he works with us on this issue with a degree of

urgency that is infectious. I think that gives all of us the ability

to work, whether with a particular industry or internationally, with

that sense that this is something the president is ready to fight for.

Share "A Sea Change On Climate Change"