In “Eating History,” food expert Old Smokey and collector Josh Macuga uncover unique vintage foods and edible artifacts that have survived for decades. But their quest isn’t only to see how well the stuff survived—or what it tastes like. Each of these consumables has an intriguing back story, with visionary creators or promoters, and history that captured the American imagination. Here are some of the fascinating facts behind each week’s featured foods:

Eating History: Food Facts

1979 / Fritos

From Roadside Stand to Mass Production: The three main ingredients for Fritos—corn, oil, salt—haven't changed for almost 90 years. In 1932, Charles E. Doolin, owner of a Texas confectionary, discovered a Mexican man at a gas station selling fried masa (cornmeal) chips, popular street food in Mexico. Doolin borrowed $100 from his mother to purchase the recipe for the “fritos” (Spanish for “little fried things”) and began making 10 pounds of them a day in his home kitchen, with her help. Soon he was mass-producing them, using assembly line techniques similar to Henry Ford’s.

Fritos vs. Tortilla Chips: Why do Fritos taste so different from tortilla chips if they are both made of corn? Fritos are corn chips and made of cornmeal, which is ground corn mixed with salt and water, then shaped and fried. The corn in tortilla chips, by contrast, is typically more processed: first, it can be soaked and cooked in an alkaline solution (such as lime water), then hulled, ground and made into tortillas. The tortillas are then cut into their desired shape and fried.

The Changing Mascot: Over the years, the Fritos brand has had several mascots: From 1952 to 1967, it was the “Frito Kid.” For the next four years, it was the “Frito Bandito,” created by Tex Avery (the famous animator behind Bugs Bunny, Daffy Duck, Porky Pig and Speedy Gonzales) and voiced by Mel Blanc, who also voiced Bugs Bunny. In 1971, the brand briefly launched the short-lived “Muncha Bunch,” a group of snack-hungry cowboys. And a year later, the company introduced “W.C. Fritos,” a character inspired by the famous comedian W.C. Fields, complete with a top hat and a cane.

1913 / Commemorative Civil War Hardtack

Tough Stuff: Hardtack, a dry simple biscuit historically fed to soldiers, dates back to ancient Rome. Made with flour, water, and a bit of salt, it’s baked repeatedly—to suck out as much moisture as possible and to keep it from spoiling.

Battle Camp Recipes: During the Civil War, a daily ration was nine or 10 crackers, depending on the regiment. Soldiers nicknamed them jawbreakers, teeth dullers and worm castles, since they were hard as rocks and often riddled with weevils or maggots from poor storage. Some soaked the cracker in coffee or water to soften it before eating; others crumbled it up into soups. Still others tried smashing them with rifle butts and then mixing in river water to make a mush—which could be cooked into a lumpy pancake if a frying pan was available. For dessert, they sometimes crumbled it with brown sugar and hot water—or whiskey, when available.

Commemorative Crackers: This hardtack was likely collected as a souvenir of a 1913 Civil War reunion event. Between June 29 and July 6 of that year, more than 50,000 veterans convened at Gettysburg, Pennsylvania to commemorate the 50th anniversary of one of the most pivotal battles in American history. These two pieces of hardtack were found wrapped in the June 29, 1913 edition of the New York American newspaper, with the inscription: "Keep Geo. W. Lewis, Moses Burchest, S.F. Liscom Present / Gettysburg July 1913 / Hard Tack or Bread/ Reunion Anniversary Battle Gettysburg July 1913.”

1930 / Pepsodent

Ancient Toothpaste Was...Crunchy? Research suggests that, as far back as 5000 B.C., ancient Egyptians used dental creams that included crushed and powdered ingredients such as eggshells, myrrh (a natural resin), and pumice (a volcanic rock), along with the ashes of oxen hooves. Ancient Romans tried even more abrasive materials, such as crushed bones and oyster shells, flavored with things like charcoal and bark. In ancient China and India, meanwhile, tooth powders and creams featured ingredients such as salt, ginseng and herbal mints.

Advertising Boosts America's Dental Hygiene: In the early 1900s, few Americans brushed their teeth. That was before a prominent American ad man named Claude C. Hopkins started hawking minty, fizzy tooth-cleaning products under the brand “Pepsodent”—named for pepsin, a digestive agent designed to break down food deposits. A decade after Hopkins’ advertising campaigns about the “Pepsodent smile,” free of ugly “film” (a.k.a. plaque), pollsters found that toothbrushing had become a daily ritual for more than half the population.

Fizzy—and False: This Pepsodent container, from 1930, claims it “contains irium,” which allegedly promoted dental health and good-smelling breath. One ad even claimed it “makes teeth twice as bright.” The problem? Irium was a made-up name for what was likely Sodium Lauryl Sulfate, now a common foaming agent in personal products. In reality, “irium” added zero cleaning power, but helped trigger a psychological reward cycle (fizzing=clean feeling) that helped people develop the brushing habit before bed. By the 1950s and 1960s, “irium” disappeared from ingredients and promotion lists.

Episode 2: Breakfast of Champions

1947 / Wheaties

Accidental Beginnings: Wheaties cereal was invented in 1921 when a health clinician accidentally spilled wheat gruel on a hot stove and watched it morph into crispy wheat flakes. Their original name? “Washburn’s Gold Medal Whole Wheat Flakes.”

Before the Athletes: While Wheaties has had an iconic and enduring relationship with sports stars, the first character connected to the brand wasn't an athlete or even a real person. It was Jack Armstrong, the "All-American boy" and star of a fictional radio show that began in 1933, sponsored by Wheaties. In the stories, Armstrong was a popular athlete at Hudson High School who traveled the world, plunging into one adventure after another—recovering lost uranium, rescuing passengers from a sinking ship and being trapped in a cave of mummies.

Jocks on the Box: In 1934, baseball legend Lou Gehrig became the first athlete featured on the Wheaties box—but on the back. The first athlete to grace the front of the box, in 1958, was Olympic gold-medal-winning pole vaulter Bob Richards, also known as the “vaulting vicar” because he was an ordained minister. In the decades since, the famous “Breakfast of Champions” box has leveraged scores of sponsorship deals with iconic athletes from Muhammad Ali and Mary Lou Retton to Brett Favre and Michael Phelps. The athlete who has appeared on the most Wheaties boxes? Michael Jordan, with 18.

1973 / LRP Ration

Portable Military Meals: This Long Range Patrol (LRP) Food Packet is a freeze-dried, restricted-calorie field ration meant to support military special-operations teams. Because they were carried into the field for days at a time, by fighters who were often on foot, they needed to be lightweight and take up minimal pack space. So they were designed as a one-menu bag per fighter per day.

Crowd Pleasers? Menu options included entrees such as beef stroganoff with noodles, oriental spicy chicken and turkey tetrazzini. Meals needed water to be reconstituted.

For Longer Missions: A long-range reconnaissance patrol, or LRRP (pronounced “lurp"), is a small, well-armed military unit that penetrates deep into enemy territory, providing advance eyes and ears for combat operations. The military introduced the LRP ration during the Vietnam War. Much lighter than a C-ration, it was issued to some units for long patrols or combat operations. This package is rare, because the LRRP ration disappeared when stocks were depleted after the war, when a new, even lighter set of rations took its place during the conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan.

1982 / ET Candy

Sweet Product Placement: E.T., The Extra-Terrestrial premiered on June 11th, 1982, amidst a severe recession in the United States. Directed by Steven Spielberg, the film permanently changed movie marketing tie-ins with a landmark product-placement deal for Reese's Pieces peanut butter candies. Spielberg originally wanted to use M&Ms as the candies that helped lure the alien E.T. back to Elliott's house. But Mars, which owns M&Ms, passed on the opportunity. The Hershey Company, which wanted more exposure for its new Reese's Pieces, agreed, and some estimates say saw profits for Reese's Pieces jump by 65 percent just two weeks after the movie's premiere.

Commemorative Candy: This E.T. Candy, a separate merchandising tie-in, was made by Topps, known for chewing gum, candy and collectibles.

A Blockbuster Movie: By 1983, E.T. surpassed Star Warsas the highest-grossing film of all time. By the end of its theatrical run, it had grossed $359 million in North America and $619 million worldwide.

Episode 3: Expiration Unknown

1977 / Billy Beer

'Professional Redneck': William ‘Billy’ Carter, younger brother to President Jimmy Carter, was a Plains, Georgia gas station owner and self-styled hard-drinking “good old boy.” Known for his buffoonish personality—which contrasted sharply with that of his earnest brother—he occasionally engaged in outlandish public behavior, once even urinating on an airport runway in front of reporters and foreign dignitaries. Billy, who profited from his brother’s position as a beer promoter, was dubbed by the Associated Press as a “professional redneck” remembered for sound bites like, “I got a red neck, white socks and Blue Ribbon beer.”

Billy Beer: During the first two years of the Carter presidency, Falls City Brewing Company reportedly paid Billy $50,000 to endorse Billy Beer, which was made for two years. Each can bears the legend, “BREWED EXPRESSLY FOR AND WITH THE PERSONAL APPROVAL OF ONE OF AMERICA’S ALL-TIME GREAT BEER DRINKERS—BILLY CARTER.” Below the logo is the quote: “I had this beer brewed up just for me. I think it’s the best I ever tasted. And I’ve tasted a lot.” In private, or after having a few too many, Carter often admitted to drinking Pabst at home.

A Barefoot Hazard: This can has the old-style "pop-top," which caused injuries when people pulled the sharp detachable metal tabs and discarded them on roadsides, beaches and parks. In 1975, stay-on tabs for aluminum cans began being used, reducing litter and injuries.

1938 / Cracker Jack

Birth of a Beloved Snack: One of America’s first mass-produced “junk foods,” Cracker Jack was popularized by Frederick William Rueckheim, a German immigrant who started selling caramelized popcorn on the streets of Chicago in the 1870s. His brother Louis is credited with figuring out how to separate the sticky-crusted kernels. The snack’s innovative “triple-proof” wax-sealed cardboard packaging appears to have been the first of its kind, allowing for mass distribution at a time when snack foods were typically sold in bulk, bags, jars or tins.

CJ Mascots: Cracker Jack’s most famous mascot, who first appeared on the front of the package in 1916, was Sailor Jack and his dog, Bingo. The boy was based on the Rueckheim brothers’ nephew Robert, who tragically died of pneumonia at age 8. Bingo, meanwhile, was modeled after Russell, the stray adopted by the company’s co-owner. Before Sailor Jack, the company mascots were two mischievous bears shown doing everything from fishing to playing baseball to climbing the Statue of Liberty.

A Prize in Every Box: At first, starting in 1910, Cracker Jack tried to appeal to adult customers by putting coupons into its boxes redeemable for goods like watches, cutlery and sewing machines. But in 1912, after the company switched gears to appeal to kids with in-box prizes, sales soared. In the century-plus since, Cracker Jack offered thousands of prizes—from tin whistles to handheld puzzles to baseball cards. In 1914 and 1915, they splurged for a collectible set of baseball cards that included later Hall of Famers like Ty Cobb, “Shoeless Joe” Jackson and Honus Wagner. Full sets of cards from either year are highly collectible and have sold for upward of $100,000.

1919 / Hagee’s Cordial Cod Liver Oil

The Original Cure-All: The use of cod liver oil as a digestive aid and healing tonic goes back centuries. In the Viking Era, between the late 700s and 1100, the Norsemen consumed cod livers to help them endure longer stretches at sea. They also reportedly used oil from cod livers as a balm for sore muscles and joints. By the 1700s, infirmaries and apothecaries began prescribing the oil as a cure-all for a wide array of conditions: rheumatism, rickets, joint pains, colds and to help heal wounds.

Hold Your Nose: But to get the benefits, you had to endure the yucky flavor. A brand called Hagee’s claimed to have solved that dilemma with their Cod Liver Oil Cordial, masking the taste with a shocking 8 percent alcohol. Hagee’s was produced by Katharmon Chemical Company in St. Louis, Missouri, which patented “Proprietary Medicines for the cure of certain named diseases” in 1904. Shortly afterward, their Cod Liver Cordial Compound began being written up in various medical journals as a way to heal poor appetite, diarrhea, tuberculosis, inflammation and other digestion issues.

Tipsy Kids?: The bottle lists the alcohol content at 8%, similar to today’s strong beer. Even so, the recommended dosage for adults and children alike was a tablespoon three to four times a day.

READ MORE: 7 of the Most Outrageous Medical Cures in History

Episode 4: Apocalypse Chow

1980 / Duncan Hines Cookie Mix

The Man Behind the Mix: Duncan Hines, whose name graces cake-mix boxes worldwide, wasn’t a chef or master baker. This son of a former Confederate soldier was a traveling salesman always anxious to find a good meal on the road. So before the interstate highway system spawned predictable chain restaurants, Hines became a self-made restaurant critic, writing detailed reviews and compiling them into high-selling books snapped up by salesmen, honeymooners and other travelers. His Adventures in Good Eating, self-published in 1936, cemented his name as one of America’s most trusted names in food. In 1952, he franchised that name to a variety of packaged food products; in 1957, Procter & Gamble bought the franchise.

First Run Snack: This box comes from the first production run of this cookie mix, which didn’t hit supermarket shelves until August of 1981.

Birth of an Iconic Cookie: The chocolate chip cookie was famously invented at the Toll House Inn in Massachusetts. One day, while baking a batch of Butter Drop Do Cookies, Ruth Wakefield—chef, educator, dietitian and, with her husband, proprietor of the inn—was looking to adapt the recipe with a chocolate flavor. She didn’t have unsweetened chocolate on hand, or time to melt it with the butter, so she improvised, using an ice pick to chop up a Nestle semi-sweet chocolate bar and sprinkling the bits into the already-formed dough. The new cookie (original name: the Toll House Chocolate Crunch Cookie) took off and Wakefield got a spot on the Betty Crocker radio show, helping to spread the new cookie craze across the nation.

1962 / Civil Defense Survival Crackers

The Cuban Missile Scare: In October 1962, after the U.S. discovered that the Soviet Union placed nuclear missiles on the island of Cuba, 90 miles south of America’s mainland, leaders of the U.S. and the Soviet Union engaged in a tense 13-day political and military standoff. Many Americans feared the world was on the brink of nuclear war.

Fallout Shelter Food: Another thing that happened in October of 1962: This case of Civil Defense crackers was packed and sealed. Created to be used in the worst possible scenario, it still sits—fortunately for the world—unopened. Such crackers were part of a Cold War campaign to get Americans to prepare for “the big one.” In 1955, the Federal Civil Defense Administration launched its “Grandma’s Pantry” campaign, which touted that Grandma was always prepared for any eventuality, so you should be too. A good provider, it suggested, stored a seven-day supply of food and water in their family bomb shelter in case of emergency or attack. Retailers like Sears mounted in-store government-produced “Grandma’s Pantry” exhibits. Ad campaigns displayed headlines including “Take these steps now to save your family.” Women’s magazines wrote articles on how to prepare your family for a nuclear attack.

Bully for Bulgur: When looking for a long-lasting, shelf-stable provision, the government turned to bulgur wheat, which had reportedly lasted thousands of years in the Egyptian pyramids. The initial plan was to create hundreds of millions of containers and place them throughout the country’s government fallout shelters—in underground shelters, caves and mountain shelters. It became a country-wide effort, with even Boy Scouts helping to find available shelter spots.

The Cracker-Making Consortium: The nation’s one bulgur processing plant couldn’t pump out the survival crackers fast enough. So cereal companies across the country—Nabisco, The United Biscuit Company of America (later Keebler), and the Kroger Company—were called upon to mass produce them as quickly as possible. Each company packaged the crackers differently, but the cracker itself was fairly similar: one 700-something calorie cracker designed to be used as one ration of food. In total, about 20 billion crackers were produced overall. The Kroger Company based in Ohio created the case we have.

READ MORE: At Cold War Nuclear Fallout Shelters, These Food Were Stocked for Survival

1947 / Grasshoppers

Exotic Foods: After a German Jewish immigrant named Max Ries moved to Chicago from Germany in 1939, he started selling imported European cheeses from the back of his station wagon. It evolved in the 1940s into Reese Finer Foods, which sold imported delicacies and exotic foods from beyond America’s borders: from pâté de fois gras and kangaroo steak to an insect line that included Japanese fried butterflies, chocolate-covered South American ants and canned hornets. Later the company started its own farm, introducing Americans to foods like baby corn and mini watermelon.

Pitching Bugs: In 1955, Ries hired Bela Lugosi to promote his "Spooky Gift Set," which was full of overstock insect inventory, including fried grasshoppers and chocolate-covered ants. And in 1960, the company president Morris Kushner went onto the Groucho Marx TV show to talk about their insect delicacies like roasted caterpillars. Reese is still in business today, but no longer sells grasshoppers.

Grasshoppers vs. Beef: More than a quarter of the world’s population eat bugs as part of their standard diet; grasshoppers have high nutritional value compared to, say, beef—high in protein and essential amino acids, with no fat or cholesterol.

Episode 5: Once You Pop

1976 / Pringles

Revolutionizing the Chip: In 1956, Procter & Gamble started developing a new kind of potato chip to address consumer complaints about broken, greasy, stale chips. The company spent two years developing an entirely new type of saddle-shaped chip and invented the tubular can as their container. However, it took them almost another decade to figure out how to make the chips taste good; Pringles finally hit the market in 1967.

Aerodynamic Food: The chips’ signature saddle shape is mathematically known as a hyperbolic paraboloid. Pringles’ designers reportedly used supercomputers to ensure that their aerodynamics would keep them in place during packaging and that they wouldn't break when being stacked on top of each other.

Not Exactly a Chip: Pringles aren’t actually sliced from potatoes; they’re made from dehydrated potatoes and mixed into a kind of potato dough with water, salt, oil and sugar. In 1975, the Food and Drug Administration declared that P&G could not officially call them “potato chips”; they would have to call them “potato chips made from dried potatoes.” Now they are listed on the can as “potato crisps.”

That ‘Stache: The character on the Pringles can, “Julius Pringles,” has a mustache made in the shape of a Pringles chip.

1957 / Korean War Fruitcake Ration

The Forgotten War: The Korean war has sometimes been referred to as "The Forgotten War" or "The Unknown War" because of the lack of public attention it received both during and after the conflict—especially relative to the global scale of World War II, and the subsequent angst of the Vietnam War. The United States, which was involved militarily between 1950 and 1953, never formally declared war on Korea; conducted under the auspices of the United Nations, the operation was deemed a “police action” by President Harry S. Truman.

An Unresolved Conflict: Fighting ended on July 27th, 1953, when the Korean Armistice Agreement was signed. The agreement created the Korean Demilitarized Zone (DMZ) to separate North and South Korea, and facilitated the return of prisoners. No peace treaty was ever signed, so the two Koreas are technically still at war.

A Taste of Home?: Every fighting force throughout history has struggled to feed their troops nutritional fare that has a taste of home—something that reminds them of what they’re fighting for. U.S. troops were partial to canned fruit, canned fruit cocktail, canned baked goods like pound cake and cinnamon nut roll, and canned meat items like ham slices and turkey loaf. It’s unclear whether fruitcake, which is often joked about as one of the most re-gifted holiday treats, was ever on the troop ration hit parade. Traditionally made with some combination of rum, dried and candied fruit, toasted nuts, butter, ginger, sugar, lemon and eggs, fruitcakes are designed to last longer than a standard cake, making them good fodder for military rations.

Flinging Fruitcake: Every December 26, Manitou Springs, Colorado hosts a huge ‘Fruitcake Toss Day’ contest to see who can throw their fruitcakes the farthest—and with the greatest accuracy. People build catapults, slingshots, or just hurl the cakes by hand.

1993 / Crystal Pepsi

Confusing Cola: As a part of the soda wars of the 1980s and ‘90s, Crystal Pepsi became a pop-culture legend for its marketplace failure. First introduced in the early 1990s in Europe, Crystal Pepsi released in the U.S. and Canada in 1992 as a caffeine-free, clear alternative to Pepsi. A giant launch campaign included a grandstanding Super Bowl ad that did little more than confuse consumers; parodies and jokes quickly followed. In 1994, Crystal Pepsi was discontinued and the experiment deemed a failure.

Crystal Revival: Decades later, Pepsi became one of the first brands to capitalize on ‘90s nostalgia. With the help of viral videos and YouTube, Pepsi created something of a revisionist history where the failure of Crystal Pepsi turned it into a rare, hard-to-find collector’s item. Widely derided in its original incarnation, the soda morphed into something “cool” and “nostalgic.”

On the Trail: Pepsi introduced a contest in December 2015 to win revamped bottles of Crystal Pepsi. The next year, Pepsi reintroduced a limited run of the infamous Crystal Pepsi, much to the happiness of ‘90s nostalgia lovers. The relaunch was a massive success, selling out in stores quickly and spawning an Oregon Trail-themed game from Pepsi called “The Crystal Pepsi Trail.” Two more re-releases of Crystal Pepsi followed in 2017 and 2018.

READ MORE: How the ‘Blood Feud’ Between Coke and Pepsi Escalated During the 1980s Cola Wars

Episode 6: From a Galaxy Far, Far Away

1950 / Tootsie Roll

Tootsie's Origins: The taffy-like chocolate-flavored treat was invented by Leo Hirschfield, a European emigre and son of a candy maker, while he was working for Manhattan-based candy manufacturer Stern & Saalberg in 1896. He named it after daughter Clara, whose nickname was "Tootsie."

Treats for the Downtrodden: In 1917, the candy maker changed its name to The Sweets Company of America, and thrived during the Great Depression by making its treats an affordable indulgence (a few pennies) during a time when many Americans could barely buy essentials. The company even expanded its line, introducing the Tootsie Pop in 1931.

Battlefield Boost: Because Tootsie Rolls were touted for their ability to retain firmness and freshness even in the hottest weather (and not melt like other chocolates), the U.S. military contracted with the company to produce the Tootsie Roll for WWII troop rations. Even as many candy companies faced hardship due to wartime sugar rationing, The Sweets Company did a booming business creating what were, in essence, energy bars for soldiers. Tootsie Rolls remain in military rations to this day.

When Tootsie Rolls Saved Lives: The candy became an unlikely hero during the Korean War. In December 1950, in brutal subzero temperatures, the 1st Marine Division found themselves vastly outnumbered and fighting for their lives at the Chosin Reservoir in North Korea. With fuel lines in their vehicles frozen, they couldn’t evacuate and were running dangerously low on ammo. But when they frantically called for more 60mm mortars, using the code name “Tootsie Rolls,” the radio operator on the other end didn’t have the code sheet; so what arrived via airdrop were not crates of the mortars—but crates of actual Tootsie Rolls. The mistake became a blessing in disguise as the subzero temperatures had frozen their rations, and they could thaw a frozen Tootsie Roll in their mouths after about 20 minutes. They also used warmed Tootsie Rolls as a kind of putty to seal cracked fuel lines in their vehicles and, by some reports, even as a temporary plug for bullet holes. Survivors agree that Tootsie Rolls were the only thing that kept them alive to trek 78 miles to the nearest port to be evacuated.

1945 / Horn & Hardart Coffee

Marvels of Efficiency: Horn & Hardart’s Automat restaurants revolutionized the American food-service industry—serving fast food decades before American fast food chains emerged. Inside each coin-operated glass compartment of the establishment’s signature gridded wall, patrons found sandwiches, slices of pie and comfort food ranging from chicken pot pie to baked beans and macaroni and cheese. Behind the scenes, kitchen staff worked speedily to refill empty compartments, racing to feed busy city workers with shrinking lunch hours. While some bemoaned the loss of a more civilized dining experience, the automats appealed to frugal diners—it was especially popular during the Depression—since there were no waiters to tip and prices for most dishes held steady at five or 10 cents. Horn & Hardart hit its peak at the start of World War II; in 1941, the business had 157 retail shops and restaurants in the Philadelphia and New York areas, and served 500,000 patrons daily.

Starbucks Before Starbucks: Horn & Hardart was the first New York restaurant chain to offer its customers “always fresh-brewed” coffee. Employees were instructed to discard any pots that had been sitting for more than 20 minutes. The practice is said to have inspired Irving Berlin to compose the song "Let's Have Another Cup of Coffee.” The song quickly became Horn & Hardart's official jingle.

READ MORE: The Automat: Birth of a Fast Food Nation

1984 / C-3PO's

Pop-Culture Crunch: Advertised on TV as “a crunchy new force at breakfast,” C-3PO's Cereal, a blend of oats, wheat and corn manufactured by Kellogg’s, first hit grocery stores in 1984. That was one year after the release of Return of the Jedi, the third installment in the original Star Wars trilogy—as the franchise was well into its pop-culture ascendancy.

Giveaways: The breakfast product, shaped like a figure 8, was advertised with a series of commercials featuring Anthony Daniels as C-3PO, offering bowls of his cereal to kids and intergalactic creatures alike. Some boxes came with cut-out Star Wars character masks (six in all), stickers, trading cards or plastic rebel rockets.

A Droid to Remember: Daniels, the actor who plays C-3PO (See Threepio), is the only actor credited as having made an appearance in every one of the nine episodic Star Wars films. The metallic, humanoid droid, originally built by Anakin Skywalker, knows more than 7 million forms of communication and is something of a worrywart.

After the Force: After severing the cereal's ties to Star Wars, Kellogg’s renamed it Pro-Grain and promoted it with sports-oriented commercials. That was also fairly short-lived.

Episode 7: A Space Odyssey

1985 / Harley-Davidson Wine Coolers

Extending the Brand: In the mid-1980s Harley-Davidson, a motorcycle company best known for making big, loud motorcycles, began a series of brand extension deals to transform its iconic bikes into an iconic lifestyle brand. Merchandise ranged from leather vests, bandanas and removable tattoos to perfume, Barbie dolls and wine coolers.

Training Wheels for Wine: Wine coolers emerged as one of the hottest trends of the 1980s, along with shoulder pads, leg warmers, mom jeans and Walkmen. Riffing on traditional hybrid wine drinks like sangria and spritzers, brands like Bartles & Jaymes, California Cooler and Seagrams became ubiquitous, mixing low-alcohol, non-premium wine with fruity flavored soda. Another company, Sun Country Coolers, enlisted celebrity endorsers ranging from Ringo to Charo to Grace Jones. In 1991, the wine cooler market, especially popular with teens, took a dive after the federal government boosted excise taxes on wine from 17 cents to just over $1 per gallon.

King of the Cruisers: The Harley-Davidson company is one of the oldest and most recognizable motorcycle brands in the world. It began in Milwaukee, Wisconsin in 1901 when William S Harley drew up a design for a motorized bicycle. After being just one of two U.S. motorcycle companies to survive the Great Depression, Harley in 1941 had its factory stop working on civilian machinery and focused solely on producing vehicles for the army. After the war, former servicemen who’d grown accustomed to Harley started transforming and modifying stock motorcycles for a more personal and individual ride experience, helping facilitate the birth of Harley’s signature heavyweight custom cruisers.

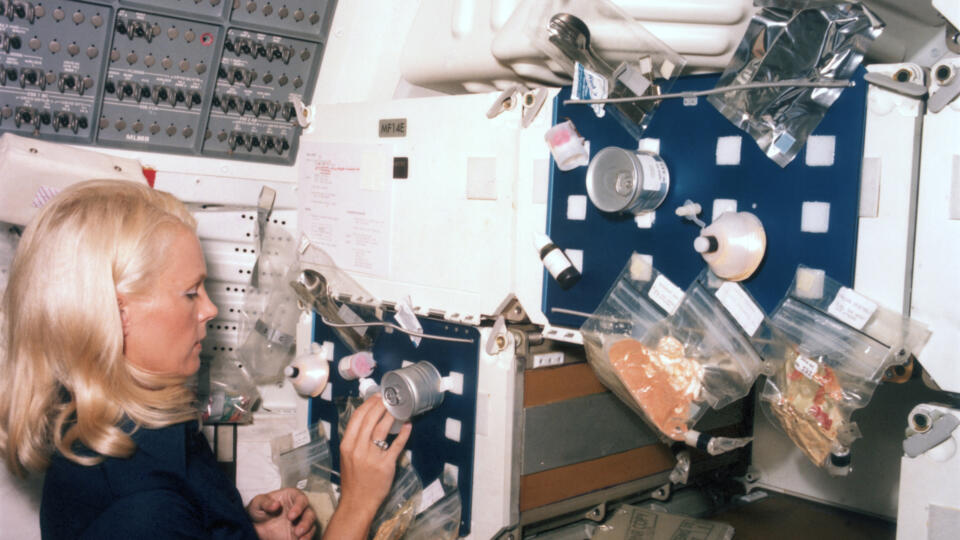

1992 / NASA Potatoes

Spuds in the Sky: Along with being the first food grown in space aboard the Columbia Shuttle, potatoes are the food NASA scientists have developed and evolved most, one of the foods that allowed for the first American to reach the moon.

Just Add Water: Potatoes au gratin like these were part of the menu on space shuttle flights launched between April 1981 and January 1986. For the first few shuttle flights, the food pouches were heated in a suitcase food warmer, which was like a metal suitcase with hotplates inside. Later flights had ovens aboard the shuttles.

Food in a Tube: In the early days of the space program, food for Project Mercury flights (1961—1964) was based on Army survival rations, which consisted of pureed food packed into aluminum tubes and sucked through a straw. John Glenn, America’s first man to orbit the earth, circled the planet three times in a 4 hour, 55-minute mission, along the way eating applesauce packed in a toothpaste-like tube and sugar tablets with water. While Glenn and the other astronauts had no problem chewing, drinking, swallowing or digesting, the food wasn’t exactly considered delicious.

Crumbs Not Allowed: The first time an astronaut ate solid food in space was on Gemini 3, when John Young snuck a corned-beef sandwich from a local Cocoa Beach deli onto the spacecraft, tucked into his spacesuit pocket. At one point during the five-hour mission, Young offered some to his colleague, Virgil Grissom, but the enjoyment didn’t last long, because the sandwich was producing crumbs. Crumbs were considered dangerous, since they could clog air vents, contaminate equipment or get stuck in an astronaut’s eyes, mouth or nose, jeopardizing the safe operation of the spacecraft. The sandwich was later dubbed “the $30 million sandwich.”

READ MORE: How Space Food Has Evolved—And Improved

1946 / Minute Rice

Early Convenience Food: The process of pre-cooking rice, drying it out and packaging it on a mass scale was developed and pitched to an executive of General Foods Corporation in 1941. He liked it, and the product, Minute Rice, hit shelves that very same year.

Helping Women Juggle: Minute Rice couldn’t have come at a more perfect time. With the bombing of Pearl Harbor later in 1941, U.S. soldiers began shipping out to fight in World War II, upending the roles and routines of the majority of Americans, and leaving women to manage home, family and finances. Minute Rice (the box actually states “Cooks in 5 minutes”) provided American G.I.s in WWII a “taste of home for those fighting for freedom in Europe and the South Pacific.” It also offered convenience for women entering the workforce—some for the first time—who still needed to provide a wholesome meal for their families.

Episode 8: The Candy Man

1980 / Chef Boy-ar-dee Lasagna

A Pioneer of Ethnic Cuisine: Chef Boy-ar-dee isn’t just a character on a supermarket can of pasta. Hector Boiardi was a celebrity chef long before they were a thing, the first ambassador for Italian cuisine to the broader American culture. After arriving at New York’s Ellis Island in 1914 from his hometown of Piacenza, Italy, Hector worked his way up the ranks at New York’s Plaza Hotel, eventually becoming head chef. He then traveled the country working as a star chef (including catering Woodrow Wilson’s wedding reception), before settling in Cleveland in 1924, and opening his restaurant “Il Giardino d’Italia,” meaning “Garden of Italy.” Il Giardino quickly became one of Cleveland’s top eateries, specializing in Chef Hector’s popular made-to-order spaghetti.

Mangia, America! Initially offering the first “doggie bags” of its day by canning people’s leftovers, Boiardi in 1928 went on to launch the Chef Boiardi Food Company, producing packaged foods like spaghetti dinner, complete with a canister of grated parmesan, a box of spaghetti and a jar of sauce. It was the first time Italian food was being offered to a mass market outside of America’s Italian immigrant communities. Soon, A&P Supermarkets struck a deal with Hector and his brother, also a chef, to mass-produce boxed dinners for its stores across the country—and suggested that the Boiardis phoneticize the company name to “Chef Boy-ar-dee” so people wouldn’t get tongue-tied.

Pasta for the Boys Overseas: During World War II, Boiardi pivoted from civilian production to making meals for the troops. Not only had he received a hefty government contract, but his own son Mario was a sharpshooter in the U.S. Army, putting the effort close to his heart. Chef Boiardi became the largest supplier of rations during the war, with his plant in 24-hour production. After the war in 1946, Boiardi sold the brand to American Home Foods for $6 million, staying on as a consultant until the late 1970s.

READ MORE: How Canned Food Revolutionized The Way We Eat

1953 / Emergency Drinking Water

A Drink to Survive: During the Korean and Vietnam wars, American pilots and sailors were in constant danger of floating adrift in the ocean. Whether an aircraft was shot down or a ship sank, the U.S. Navy wanted its personnel to have the necessary survival equipment to make it as long as possible while waiting for rescue. Cans of U.S. Government-Issue Emergency Drinking Water, distributed in survival kits with a P38 can opener taped to the top, sometimes made the difference between life and death.

Fresh Water? To inspect these cans, soldiers often did what was known as a "Slap Test." The idea was to slap the end of the can with your hand, and if the water moving inside made a slapping sound, it passed; but if it didn’t, the water might be bad. Even when soldiers let the cans “breathe” a while between opening and drinking—the water usually still had an aluminum taste. Cans like these were used up to the late ’90s, after which most military branches transitioned to flex-pak water “Blatters.”

Fallout Shelter Essentials: Emergency water was also considered a crucial fallout shelter ration. The threat of A-bomb annihilation hung heavily over American society during the Cold War era, and people were encouraged to construct fallout shelters in their basements and backyards—stocked with at least seven days worth of food and water.

A Cure for What Ails you: America’s first commercially distributed water, bottled and sold by Jackson's Spa in Boston in 1767, predates American independence. Historically, waters from mineral springs were believed to have therapeutic properties—whether drunk or bathed in.

READ MORE: At Cold War Nuclear Fallout Shelters, These Foods Were Stocked for Survival

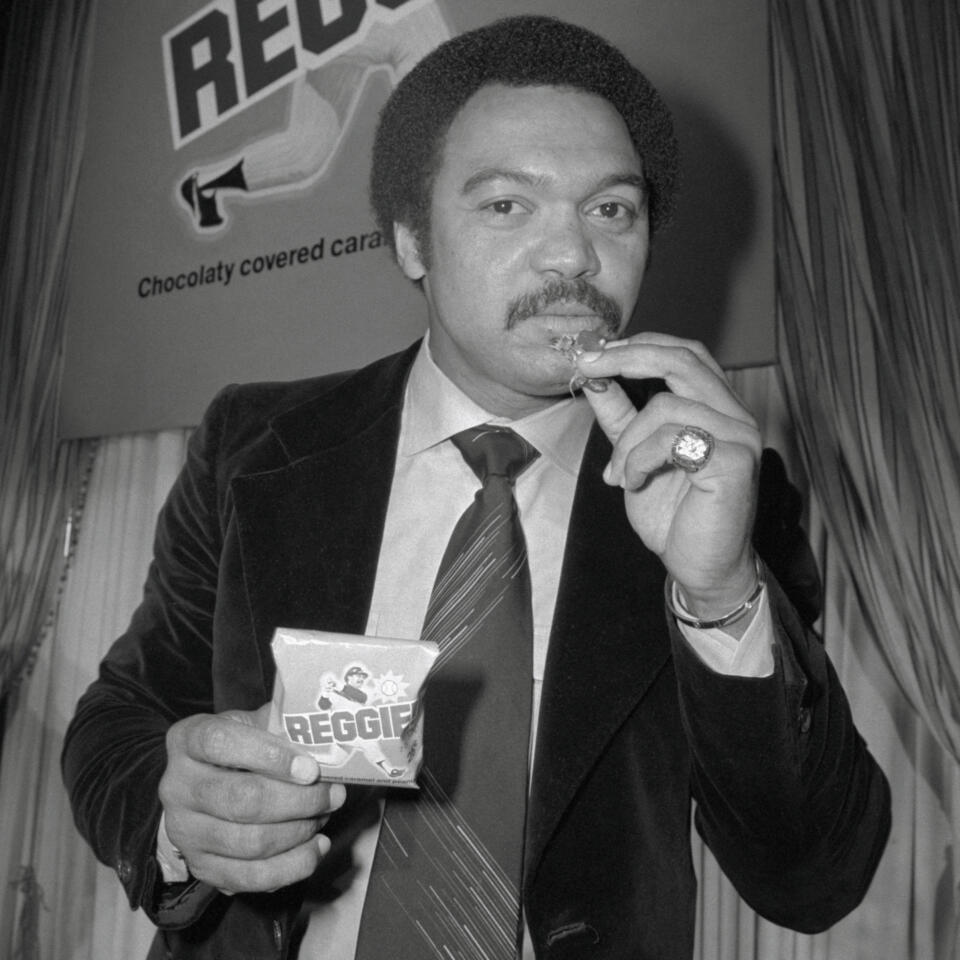

1993 / Reggie Bar

Mr. October: In 1976, Baltimore Orioles right fielder and slugger Reggie Jackson claimed, "If I played in New York, they'd name a candy bar after me." A few months later, Jackson signed a five-year, $3 million contract with the New York Yankees. He then went on to have one of the most memorable World Series performances of all time, hitting three consecutive home runs off three different pitchers...each time on their first pitch. The Yankees won, launching Jackson’s legendary nickname: “Mr. October.”

It's Raining Candy: The next season at the Yankees' home opener, Reggie finally got his candy bar, aptly named the Reggie!, a circular "bar" of peanuts dipped in caramel and covered in chocolate. Later that season, Reggie again led the Yankees to World Series glory. Fans attending the games received the bars on entering the ballpark, and when Jackson hit a homer, they tossed the candy onto the field in celebration. Jackson speculated to the press that maybe the fans didn’t like the candy.

Candy Kerfuffle: Reggie! was the first candy officially named after a baseball player. Reggie! was made by the same Chicago-based Curtiss Candy Co. that famously made the Baby Ruth candy bar. But when a lawsuit arose over naming rights, the company claimed that Baby Ruth was named after U.S. President Grover Cleveland’s daughter “Baby” Ruth—a strange claim since “Baby” Ruth Cleveland had been dead for decades before her “namesake” candy was released in 1921.

READ MORE: Babe Ruth v. Baby Ruth

Episode 9: Leave it to Beaver Tail

1989 / 3 Decades of Oreos

Oreo Evolution: The Oreo cookie (original name: the Oreo Biscuit) was first manufactured in 1912, within the walls of the Chelsea Market in New York City. With the exception of an early lemon-creme variety, which was ditched in the 1920s, the iconic sandwich cookie remained one flavor in the U.S. market—chocolate wafers surrounding vanilla creme—until the 2000s, when Nabisco started releasing limited-edition and holiday-themed flavors. Every Oreo cookie (aside from Double Stuf, Mini Oreos, etc) is created with a ratio of 71% cookie to 29% cream.

Cookie Smackdown: Oreo wasn’t the first chocolate-wafer sandwich cookie on the market. Four years earlier, Sunshine Biscuits had introduced the Hydrox, almost identical in its look and taste. But from the beginning, Oreo used lard—which comes from pig fat—in its creamy filling, which Hydrox didn’t. That made the Hydrox certifiable as kosher, edible under Jewish dietary restrictions. Oreos were not.

The Evolving Oreo Pitch: In the 1950s, Nabisco used the tagline “Oh! Oh! Oreo” to sell its popular cookies. From 1980-1990, the company went through five slogans: “For the Kid in All of Us,” “American’s Best Loved Cookie,” “The One and Only,” “Who’s the Kid with the Oreo Cookie?” and “Oreo, the Original Twister.” In 1993, the company added “American’s Favorite Cookie” to the packaging. Then in 2004, the tag line changed to “Milk’s Favorite Cookie,” which still remains today.

Going Kosher and Heart-Friendlier: In the late 1990s, after years of planning—and prodding from ice cream companies that wanted to mix the cookies into their products—Oreos were finally made without lard. The transformation to kosher involved converting a football field’s worth of baking ovens. One key step: a rabbi with a blowtorch heating each oven to red-hot temperatures to clean away the residue of forbidden materials. Another significant recipe change for the Oreo came in 2006, when Nabisco removed trans fat from its creme filling, replacing it with a blend of canola and palm oil (saturated fats). This came after the U.S. Food and Drug Administration in 2003 had announced new labeling requirements requiring manufacturers to list trans fats—which are closely linked to heart disease—on their packaging.

1962 / Survival Food Packet

Provisions for Extreme Climates: In the 1950s and 1960s, there were two basic types of military Survival Food Packets: Survival Arctic (SA) and Survival Tropic (ST). These packets included food essentials to get pilots, paratroopers and others through emergency situations until rescue attempts could be made.

What Did These Packets Typically Contain?: 1) High-caloric jelly-type concentrated food bars; 2) a few soluble coffee or tea packets; 3) chewing gum, said to be an appetite suppressant; 4) sugar; 5) an instruction sheet, with advice not only on how to eat the food, but also on how to get through an emergency. Some packets also included water purification tablets and mysterious vitamin tablets, possibly B6.

Early Days in Vietnam: In 1961, in response to escalating tensions in Southeast Asia, President John F. Kennedy sent helicopters and several hundred special forces troops and 100 other special advisers to South Vietnam, likely with versions of the ST Survival Food Packet just like this one. This version, which hails from March 1962, contains three days’ worth of emergency rations for one soldier (or one day for three soldiers).

1989 / Batman Cereal

A New Batman Rises: Tim Burton’s 1989 film Batman, starring Michael Keaton and Jack Nicholson, gave birth to the darker, more mysterious, slightly disturbed Batman—a drastic departure from the benign, campy caped crusader of the late 1960s TV show. But it also gave birth to a new kind of ultra-hyped summer superhero blockbuster event, overloaded with merchandise tie-ins. The buildup for this movie—and anticipation from fans—was unprecedented. Posters were being ripped off bus and train stations. Fans bought tickets just to go see the Batman trailer in theaters, then left before the feature film. And Prince, who wrote the soundtrack, hit #1 with a promotional “Batdance” video, featuring dancing Dark Knights and Jokers.

Cereal+Entertainment on Steroids: Ralston Foods Inc. cashed in on this soon-to-be box office hit by working to create a Batman breakfast cereal that appealed to children and adults alike. Shaped like—what else?—bats, the cereal was advertised on the box as having a “natural honey nut flavor.” Ralston Foods went full force with branded TV, movie and game cereals including Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, Prince of Thieves, Ghostbusters, G.I. Joe, Nintendo Cereal System, Urkel-O’s and Bill and Ted’s Excellent Cereal. Most had a short lifespan.

Episode 10: Flavor Explosion

1977 / Space Dust Candy

Pulverized Pop Rocks: Remember Pop Rocks, the nuggets of hard candy infused with bubbles of carbon dioxide that fizzled and gently exploded in your mouth? Invented by General Foods food chemist Bill Mitchell (who also had patents for Tang, Cool Whip and quick-set Jell-O), Pop Rocks were an instant hit when they launched in 1975—and spawned a spinoff called Space Dust Candy, a more pulverized, powdery version of the same pleasantly mouth-zinging stuff.

Unfortunate Branding: Sadly for Space Dust, its name was perilously close to “Angel Dust,” also known as PCP, a popular—and sometimes lethal—illegal drug at the time. Unwarranted associations were made, and some parents became worried that fizzy powdered candy might become a “gateway” to powdered recreational drugs. General Foods changed the name to “Cosmic Candy” to avoid any confusion.

The Bubbles Burst: There were other damaging rumors as well. One particularly fantastical story circulated that a child had died after consuming the candy with a carbonated soda, causing an “explosion” in his stomach. Things got so bad that Bill Mitchell took out a full-page ad in The Pittsburgh Press newspaper in February 1979, explaining how he started making the candy back in the 1950s for his kids, and how it was perfectly safe despite all the unfounded rumors. But it was too late: Space Dust/Cosmic Candy soon disappeared from market shelves.

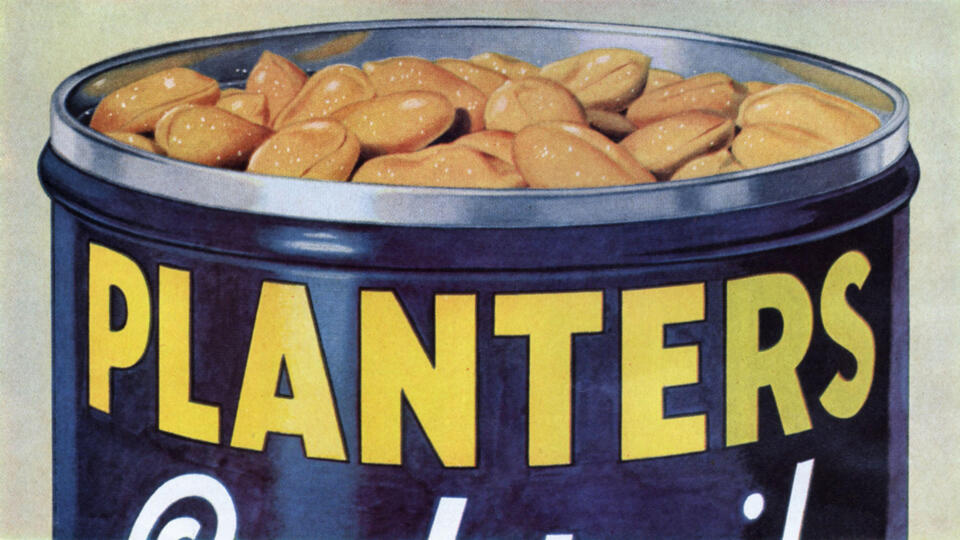

1981 / Planters Peanuts

Birth of a Peanut Giant: In 1906, two Italian immigrants living in Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania, Amedeo Obici and Mario Peruzzi, founded Planters Peanut Company, after years of experimenting with roasting and salting peanuts. By 1913, they had grown their business to the point where they built a massive processing plant in Suffolk, Virginia. In one early innovative marketing promotion, Obici inserted one letter of the alphabet into each bag of peanuts, then gave away a free bag to anyone who collected all the letters of his last name. In the 1930s, Planters stores opened in cities across the country.

Introducing the Distinguished Mr. Peanut: In 1916, Planters held a contest for a brand mascot. The winning sketch, showing a humanized legume named Mr. Peanut, came from a Suffolk-area schoolboy named Antonio Gentile. The top hat, monocle and cane came later, flourishes added by a commercial artist. After gracing peanut cans, billboards, magazine ads and TV commercials for nearly a century, Mr. Peanut earned a spot on Madison Avenue’s Advertising Walk of Fame in 2004. In 1978, fans of the iconic mascot launched a collector group called Peanut Pals, now comprising several hundred collectors across North America. The nonprofit, which took its name from a 1927 Planters advertising pamphlet, hosts an annual convention where members display and trade memorabilia ranging from old advertising posters and peanut tins to housewares and clothes.

Anniversary Tin: This “Planter’s Limited Edition Nostalgia Can,“ commemorating the company’s 75th anniversary, is an authentic replica of a 10-pound can manufactured by Planters in 1906, the year of its founding. During that time, street vendors would scoop peanuts from a 10-pound tin to sell on the streets—which explains the instructions on the side about how to sell nuts and talks about the proven digestive benefits of vegetable oil.

1987 / Chicken a la King

Food for Fighting: In the thick of battle, soldiers need rations that are not only filling, but quick, easy and quiet to open. For two decades before and through the Vietnam War, the U.S. military fed its combat troops with the Meal Combat Individual (MCI), a bulky, heavy ration consisting of canned foods. But in 1975, the Department of Defense revolutionized the way soldiers ate, developing the first MRE (Meal Ready to Eat), a lightweight, nutritional and compact alternative.

Kicking the Can: MRE food is precooked before being placed inside flexible, heat-resistant laminated plastic pouches, which are then sealed and heated at high temperatures, resulting in sterile, shelf-stable food. Lighter, flatter and more pliable than tin, these pouches, called retort packaging, can handle more abuse in the field and are easier for troops to carry in a backpack or pocket. Large-scale production of the MRE began in 1978, with delivery in 1981.

Tweaking the Ration: In 1983, the 25th Infantry Division conducted a field test, eating nothing but MREs three times a day for 34 days. While the rations were rated acceptable by troops, their consumption rate was only about 60% of the calories provided. Three years later, the same division conducted the same field test, this time with higher levels of consumption and acceptance. Based on these two field tests, the DoD made significant changes to the MREs. Among them: They replaced nine of the 12 MRE entrees, upped the entrée size from 5 oz. to 8 oz. and added commercial candies and hot sauce to many of the menu items. After more testing and feedback from Operation Desert Storm troops, new upgrades included commercial freeze-dried coffee and wet-pack fruit.