There is no sport where the lines between virtual and reality have blurred more than motor racing, and nowhere has this become more apparent than in GT Academy, a competition dreamed up by Nissan Motor Company. It started in 2008 as an attempt to recruit new talent from the massive pool of videogamers racing in their homes in front of their monitors, all over the world. It became not just a contest, but a reality TV show, in which gamers compete for a seat in a real professional racecar. This is the story of Jann Mardenborough, a shy kid from Cardiff, Wales, who in 2011 beat 90,000 competitors to earn a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity—to become a pro driver, on the world stage. As the London Telegraph reported not long ago, “In his short, whirlwind journey from racing on a PlayStation to lining up at Le Mans…Jann Mardenborough has already experienced more ups and downs than many will encounter in their entire motor racing lives.”

From Bedroom Gamer to Professional Racer

One morning in the winter of 2011, I turned on my PlayStation in my room in my family’s home. The game Gran Turismo had updated overnight. There was a new menu, and on it was GT ACADEMY TIME TRIAL. I had heard of this competition—a race for gamers. It was one car and one track for six weeks, and the top 20 lap times in six different countries would move on to the next phase.

Like so many 19-year olds, I played a lot of videogames, and my parents were always saying: You’re not playing videogames until you’ve done two hours of homework! Gaming was an escape. Ever since I was a kid, I had been obsessed with motor racing. My dad played professional soccer, and he had seen some of his childhood dreams come true. But for me, how was I going to become a motor racer? Professional drivers grow up racing karts. I did not even know that real kart racing existed. You need a tremendous amount of money to go motor racing, and I did not know anyone who had a lot of money. I had only seen one motor race. All I had was videogames.

That first night playing GT Academy, I ranked in the top 50 in the UK. I left it for a few days and when I came back, my ranking had dropped to around 50,000. For six weeks, the times kept updating every day, every hour, and the laps were getting faster and faster. For the last two weeks, I raced five hours a day. On the final night, I set my best time, and I was 9th in the UK. I went to bed thinking: I’ve done my best. We’ll see if I’m in the top 20 in the morning. The next day, I woke up and turned on the PlayStation. I was still ninth, and I received an email from Sony saying I had made it to the next round.

I ran downstairs and told my mom and dad: I had qualified. It all felt so far-fetched, a pretty cool moment.

WATCH: Full Episodes of The Cars That Built the World online now..

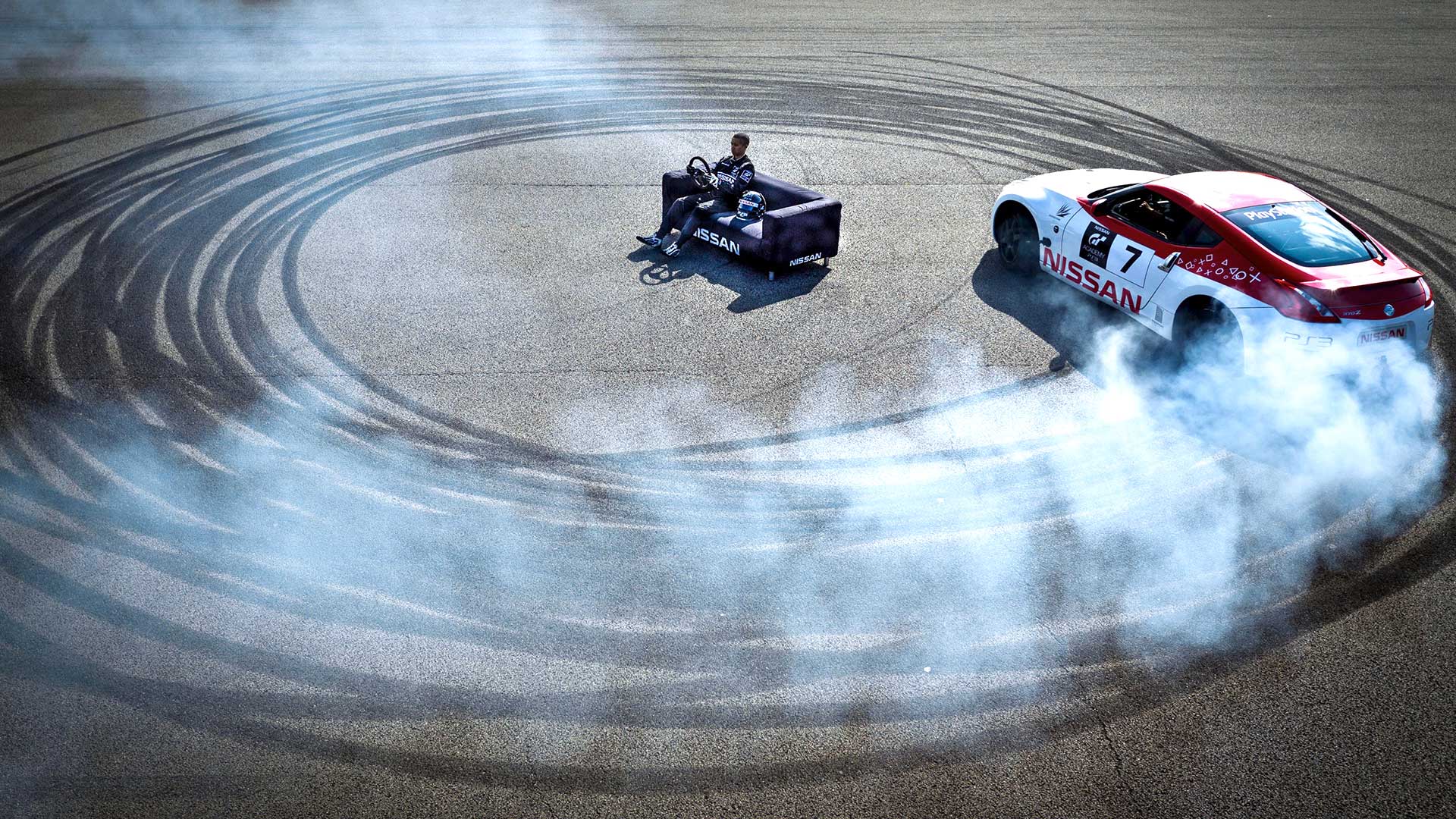

Jann Mardenborough training in 2013 in a simulator at GT Academy, Nissan’s driver-development program designed to turn the most talented video-game racers into real-life ones.

For lots of people like me, GT Academy was a once-in-a-lifetime chance, a shot at a career in motor racing. It also meant something new—that gaming was important outside the walls of the rooms where people like me played.

I was too young when GT Academy started, but in 2011, I qualified for the final, and suddenly, I was filming in a reality TV show. There were 12 of us, and the show had us competing for seven days in all kinds of ways to test our stamina, and whether we had nerves of steel. We were racing Nissan 370Zs and GT-Rs, and doing army assault training. I flew an acrobatic airplane. We were constantly being evaluated, and it was all being filmed. I had never experienced anything like this, and it was by the far the most demanding week of my 19-year-old life.

The competition finished with a final event at Britain’s most famous racetrack—Silverstone. I won the race, but that did not mean I had won it all. I was standing on the podium and Eddie Irvine—Northern Ireland’s most famous racing driver—was in front of me. I was thinking: This is cool. I’m face to face with Eddie Irvine. I remember feeling very, very anxious. If I had been asked to speak, my voice would have been trembling. Irvine made an announcement, but his Irish accent was so strong, it took a moment to register. What he said was that I had won not just the competition’s final event, but that I had won GT Academy—the entire competition. Champagne was being sprayed in my face, and all the contestants, all the judges, all the crew—everyone was going mad.

I reached for my phone in my pocket and called my mom. She was driving home from work and I said, “Look mom. I won GT Academy.” She started screaming. It was the best moment in my life. But reality hit pretty quickly: Now came an even greater challenge, to prove that Jann Mardenborough—a videogamer—could compete as a professional racecar driver.

Just seven months later, I was at the 24 Hours of Dubai, with Nissan. This was real racing, with cars capable of extreme speeds. We had a team of four drivers (one in the car at a time), and all four of us were graduates of GT Academy. It was the first time in professional racing that an all-gamer team like ours was on the grid in a professional race.

Both my parents were there and my dad was fine with it. He said, “Look, son, you’re doing something that’s your passion.” My mother was visibly nervous. [“What’s this all about?” she later put it to ESPN. “They’re talking about making a real-life racing driver from someone who’s playing a game?”] I was nervous too, but it was cool racing in another country, in the darkness, and being part of a professional team. We finished third in our class and we were on the podium, which was wild. Once my mom saw that, and she saw all the safety equipment, she was fine with it too.

Through Nissan, I took on the role of a professional racing driver, traveling around Europe, testing and racing cars. My life could not have changed more, in such a short time. It was completely bizarre. All the years playing PlayStation had prepared me in ways I did not realize—the quickness of reactions, and how to learn the idiosyncrasies of every racetrack. No two corners anywhere in the world are exactly alike, and each must be handled at a precise speed, in a precise gear, with a precise route through the turn—in a car of which no two feel exactly alike. All of that can change according to weather, or the tires, or the setup of the car, which was another thing I had learned a lot about by gaming. Meanwhile, a quarter of a second could make the difference between winning…and not even close.

Drivers motoring on the track during the early morning hours of the 2013 24 Hours of Le Mans, the world’s most elite racing competition.

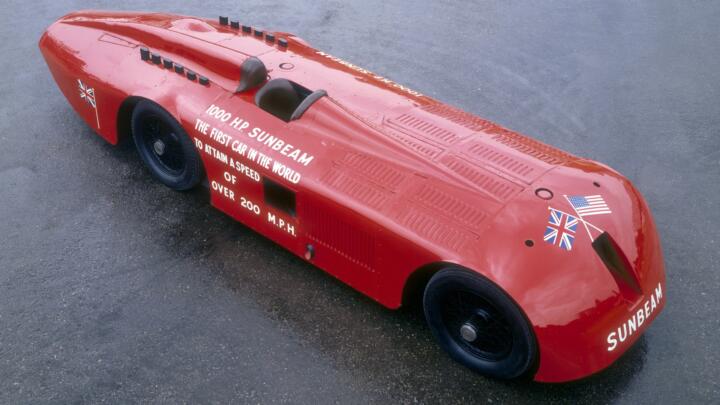

In 2013, two years after GT Academy, I raced at the 24 Hours of Le Mans for the first time—the most important sports car race in the world. There is no way to put into words what it is like speeding down the 2 ½ mile Mulsanne Straight in the dark, with cars around me hitting 200 mph, and the focus it takes to perform, corner after corner, lap after lap. Our team finished third in our class, which was unbelievable. Nissan liked what I was doing, and so in 2015, they put me in an LMP1 car—the fastest and most technologically advanced kind of racing sports car in the world, in the top class of drivers.

I was now testing in single-seaters, which is a completely different discipline, requiring more demanding physicality. When I started in Europe's Formula 3, a major open-wheel championship, a lot of people doubted me. They said I could never compete, and I liked that challenge. I liked proving them wrong. [Nissan’s Darren Cox, who headed up GT Academy, said of Mardenborough, to Motor Trend at the time: “Take Jann Mardenborough. He’s racing in Formula 3 at the moment. The guys he’s racing, some of them have been racing in Formula 3 for longer than he’s been racing. It’s his first season of single-seater racing, and he’s halfway up the grid already and he’s progressing as he goes forward. So these [GT Academy gamers] have got talent.”]

Virtual had become reality. But it was never far from my mind that, in real life, you cannot start the race over. You can no longer reach out and turn off the machine.

The aftermath of Mardenborough’s 2015 accident at Nurburgring Nordschleife in Germany, where a spectator was killed.

I was in a Nissan GT-R Nismo at the Nurburgring Nordschleife, a 13-mile track in Germany that many believe to be the most difficult challenge in motorsport, and for me the one circuit I had always wanted to race on. It had always been my favorite circuit as a gamer, and it was becoming my favorite circuit now in real life.

When the incident happened, I was on the last lap of an eight-lap stint, about to pit for fuel. We were running sixth and the car felt really good. I came over the brow of a hill and the front end lifted off. It was like when you’re in an airplane and the front wheels take flight. Only in a motor car, it’s the worst feeling you can have. Suddenly, none of your wheels are on the ground and it feels like an eternity as you brace yourself for impact.

The aftermath was a feeling I would never wish on anyone. It was life changing, and something I find hard to talk about, even three years later. [A spectator was killed and others were injured. Footage of the incident on YouTube has gotten over 8 million views, and it was covered in newspapers around the world.]

Danger is a part of racing, and always has been. At the time, I was racing in Europe with a team called Carlin, and they had my back completely. They wanted me in a car the next week, testing at a track in Wales.

When I stepped into the car a week after the crash, I did not know what to expect, but once I started driving, my thought processes were normal. I was only meant to do a 20-lap shakedown, but I ended up driving around 110 laps. Motor racing requires a focus so singular and acute that, when you are in the car, nothing else exists. And this is the place where I have come to know myself best.

For the 2017 season—six years after GT Academy—I am driving in the GT500 class of the Super GT series, the most competitive sports car series in Japan, and also Super Formula, which is open-wheel racing in Japan. [Mardenborough has signed as a development driver with Infiniti Red Bull F1 for the 2014 season, and he has raced in GP2, which is one notch below Formula 1, the pinnacle of international motorsport.

When I was growing up, I dreamed of going to three places: the U.S., Dubai and Japan. Now I have raced in all three. My favorite movie growing up was The Fast and the Furious: Tokyo Drift, and now, when I walk down streets around where I live in Tokyo, I recognize places I saw as a kid, in the movie, and I can’t believe my eyes. I have had the opportunity to go to the studios where the videogame that started it all for me—Gran Turismo—is made. I’ve met the creators, and I got to see them making the next generation. That, for a gamer, is mega. It’s part of a life I never dreamed I’d have.

But tragedy is also part of that life. Forever I will have this weight on my shoulders. Every time I step into a car, and with everything I do, I try to best represent myself and my family name and all the people around me, in the best way I can.